In Pakistan, a mere mention of the military can get a journalist in trouble. Yet some startups are bravely reporting the facts.

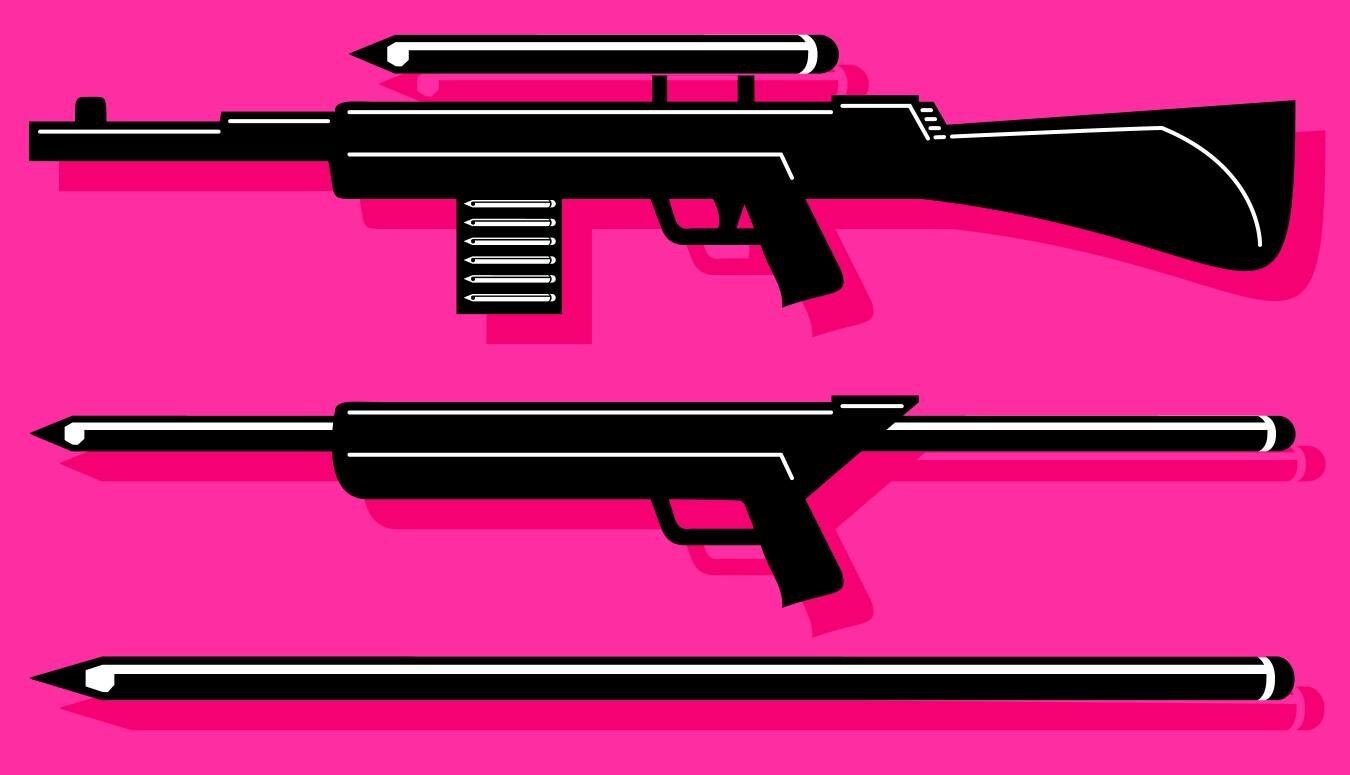

Censorship has increased so much that even the mere mention of the military can cause trouble for journalists. Illustration: Rishad Patel

In the last few years, media censorship in Pakistan — which regularly sees journalists threatened, abducted and even murdered — has caused a creeping blackout in the country, with the northern and western regions of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), Balochistan and Gilgit more aggressively targeted.

News channels have been attacked, banned and shut down for reporting on critical issues that somehow offend the military establishment. Censorship has increased so much that even the mere mention of the military can cause trouble for journalists.

Earlier this month an editor at DAWN, Pakistan’s leading English-language daily, told me that the newspaper avoids mentioning the words ‘military’ or ‘the establishment.’

Instead they fall back on vague terms to describe these institutions, such as ‘the state’ or ‘the powers that be.’

These allusions, the editor told me, are generally understood by switched-on readers — but not always by all readers.

Using this kind of non-journalistic language has become a common compromise to stave off media closures.

And such censorship not only avoids criticism of the military, but also avoids discussing the largely diverse regions that the government considers to be sensitive. These northern and western regions have become press no-go areas and include those areas where ‘the state’ has launched military operations or where the armed forces have a heavy presence.

Foreign journalists are rarely afforded access to these places. Under the pretence of security concerns, members of the press from outside the region are told it is too dangerous to travel restricted areas, further shrouding the military’s actions in secrecy.

And the message has been swallowed up by many foreign correspondents: A Washington Post reporter earnestly parroted back the official line to me recently when describing how their travel plans had been blocked.

Weathering censorship

Not only do critical security stories fall victim to censorship, but the social, civic and economic coverage of these places is also being neglected, often leading to grave challenges for the people of Pakistan.

In 2015 I was visiting a small village on the outskirts of Bannu, in the FATA region, with a local news crew. A heavy hail storm had hit, destroying crops and leaving poor farmers to deal with a major blow to their livelihoods.

As the local journalist began reporting the extent of the damage live on TV, the cameraman started getting calls from the ISPR (the media wing of Pakistan’s intelligence agency) telling him to stop the coverage and leave the area.

In Pakistan’s no-go areas, even the weather news is censored. Thus, for the nation, what is out of sight is out of mind.

So when student activist Manzoor Pashteen began a campaign for answers about the increasing number of missing persons in the country, the entire national media imposed a solid blackout.

For days, thousands of protestors sat outside the National Press Club, but the media did not cover the demonstrations until some celebrities and politicians visited and a softer angle to the story presented itself.

One executive at a leading news channel told me, “We were waiting for the others to get on the coverage first, so we don’t get the blame. And I guess all other channels were doing the same.”

New media outlets are making a difference to public understanding of the so-called ‘no-go’ regions. Illustration: Rishad Patel

Startups step up

But a new wave of media startups is interrupting the highly censored journalism landscape in Pakistan. They are filling the holes in information left by traditional media outlets, by offering on-the-ground coverage of issues the mainstream media has not been able to report.

Among them is the Waziristan Times, a news website that aims to bring “the voice of deprived community of FATA and southern districts to the nation.”

The site is run by Farooq Mehsud, who has been a local press reporter for more than a decade. Mehsud operates with almost no money and few resources. But he has found no shortage of reporters willing to contribute.

Another is the Pushtoon Times, which also operates on a limited budget and is heavily reliant on unpaid contributors.

Journalists in the region who cannot report important stories for their respective news outlets can now contribute to these independent media outlets, ensuring that issues from the student protests to IED deaths are made transparent through their reporting.

These startups have become key sources of information for media consumers, not only in the regions affected by the blackout, but also in other parts of the country.

Their images, videos and text are widely circulated on social media — perhaps, in some regions, more than those of the traditional press.

Another outlet, Hum Sub, an online platform in the local language Urdu, has become a popular space where analysts and journalists share analysis of important stories in Pakistan, most often related to the no-go areas and restricted topics.

On this forum analysts have the space to say what is usually spiked by news channels. Anything that is censored by mainstream and traditional journalism outlets in Pakistan is now being discussed on Hum Sub.

As a journalist closely following Pakistan news, often on the ground, I can see the difference these new media outlets are making to public understanding of the so-called ‘no-go’ regions.

They deserve more attention from foundations that work toward the protection of free speech.

Indeed, the most authentic way to interrupt widespread press censorship in countries like Pakistan is to empower such startups that are born out of resilience and purity of purpose.

It is small media outlets like these that offer hope amid the crumbling state of free press worldwide.

Tweet

Donors working for press freedom should be paying more attention to media startups uncovering stories amid censorship in Pakistan, says @kirannazish.